Pigot’s Commercial Directory of Ireland (1824) describes Clonmel’s Corn Market as being as extensive as any in the Kingdom. It claims that one fifth of all flour exported from Ireland emanated from one establishment in Clonmel alone. By 1832, Clonmel was the dominant force in milling nationally and was exporting a quarter a million hundredweight (approx 50kg) of flour per annum through the port in Waterford. Clonmel preeminent position was attributable to a number of factors. The Corn Laws introduced in 1815 restricted the flow of corn into the United Kingdom. This favoured domestic producers and kept the price of corn high. The Suir not only provided Clonmel with the power to operate mills but also allowed for the rapid transport of flour down river to Waterford for exportation. The fertile soil of South Tipperary provided ample raw material to turn Clonmel into a boom town during the first half of the 19th century.

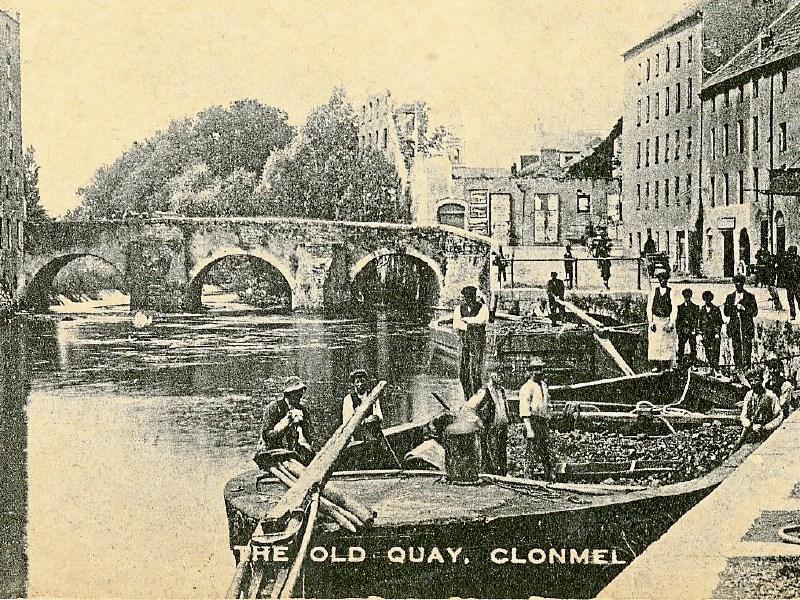

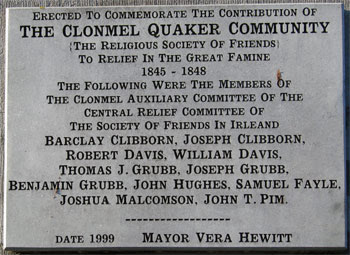

Rev. Burke in his History of Clonmel details how the population of the town doubled from 10,000 to 20,000 in this period. The number of household paying the window tax increased from 1,349 to 2,330 by 1841. The Society of Friends or Quakers were the driving force behind this huge expansion in milling. Families such as the Sparrows, Clibborns, Grubbs, Hughes and Malcolmsons all operated successful mills in and around Clonmel. Indeed the Quakers had considerable interests across South Tipperary. At its height their were seven mills operating in Clogheen and five in Cahir. Flour, wheat, oats and barley would be transported by horse and cart to the quayside in Clonmel for eventual exportation. On the eve of the Great Famine South Tipperary could rightfully claim to be the breadbasket of England.

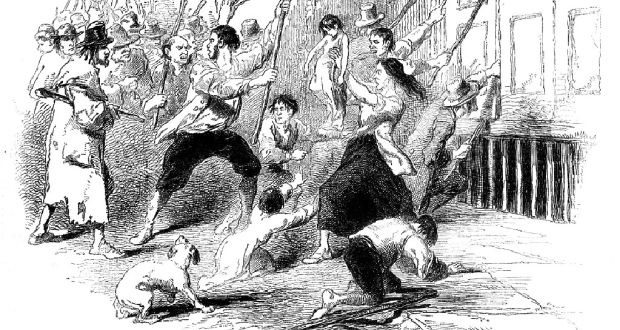

Attacks on mills and flour carts in South Tipperary are recorded as far back as 1784. The failure of the potato crop in the 1830s gave rise to spat of such incidences.

…the Clogheen carts laden with flour for this town, were a second time attacked, and ten sacks of flour forcible taken away …

The Dublin Mercantile Advertiser of the 16th of June 1834

However the onset of the Great Famine saw a dramatic escalation in the frequency and ferocity of these attacks. The people were, as one reporter described it, goaded by pangs of unappeasable hunger. A food riot broke out in Clogheen in April 1846 in which mills and bakeries were looted. At least two similar riots took place in Clonmel that same year. On the 21st of October 1846 the Tipperary Free Press reported on an ambush at Knocklofty. Men, women and children lying in wait in a nearby house attacked two loads of flour bound for Clonmel, from Grubb’s Mill in Clogheen. There are numerous reports of boats being intercepted and emptied of their contents before they had even reached Carrick-on-Suir. The merchants responded by transporting their produce in larger convoys. Some of these were up to 120 carts long. As attacks persisted the military were drafted in to provided armed escorts. Even this wasn’t enough to deter the starving. It had become a matter of life and death for the people.

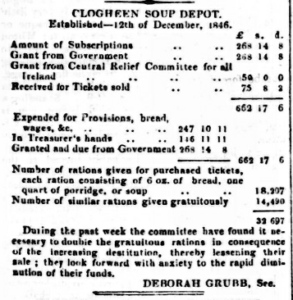

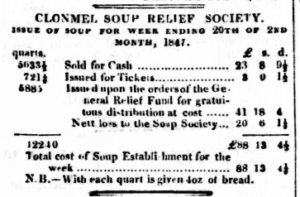

Many historians assert that no group did more to ameliorate starvation during the famine than the Quakers. Helen Hatton in her contribution to the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine argues that even though the Quakers were not the largest relief agency in the field they were the most successful. By late 1846 a relief committee had been set up in Clonmel. Between September 1846 and March 1847, 300 to 400 gallons of soup a day were being provided at their soup depot in the town. Similar depots were being operated in Cahir by the Jellico family and in Clogheen by Deborah Grubb. Unquestionably many lives were saved across South Tipperary as result of the Quaker soup kitchens. However, as one historian points out, it was

the supreme irony that the military and police defend the convoys of flour carts making their way from the Grubb family mills to be exported via Clonmel while the wives of the owners seek to defend the poor.

Atlas of the Great Irish Famine – William J. Smyth, The Famine in the County Tipperary Parish of Shanrahan

This contradiction can be viewed from a number of perspectives. The Quaker relief effort nationally was not confined to the provision of food. Providing clothing, seeds, fishing and farming equipment formed part of a broader strategy of famine relief. The Quaker community provided much needed help at a time with the government response fell woefully short. They did so out of a sense of charity and at times at a great cost to themselves. Their mills were huge sources of employment across South Tipperary during this time. The exportation of food during the famine remains a controversial subject to this day. It is argued in some quarters that Ireland was a net importer of various food stuffs (including grain) during these years. Be this as it may the death from starvation and associated disease points firmly to a population unable to access food.

It is not difficult to understand why shipments of flour became the target of attack. The assizes which took place in Clonmel in July 1846 tell their own story. 77 people were found guilty for their part in the foot riots which took place in the town the previous April. A correspondent for the Cork Examiner summed up the situation when commented

when it is remembered that, at the very time that those outbreaks took place, our streets were blocked up daily with long lines of cars conveying flour and provisions to our quay for shipment to England, it cannot be a matter of great surprise that a people famished with hunger overstep the bounds of law and prudence.

The Cork Examiner 29/07/1846